forget about state; think about events/commands

Why?

When managing state, it's easy to just think about which knobs you need to change manually. This is a low-level view of how state management works.

If the developer doesn't pay attention, the number of small states increases and also the work to keep everything in sync (since there are additional states that needs to be updated together).

There is only a finite number of commands and transitions an application really needs.

We can imagine something like:

- route to some place

- select an item from a list

- submit a form to an endpoint

And translate into code as:

class RouteTo implements Command {}

class SelectedItem implements Command {}

class SubmitForm implements Command {}

The application state

State, specially in most mainstream front-end technologies, they are all just a union of all possible states in an object available at any time.

This also means that you are adding cache or, at least, you need to set up and tear down, and, always at risk of having stale data.

It also common to shard the state into modules to separate one from another, but in some cases, you need to run actions for each of the states, causing many requests to render for a single event.

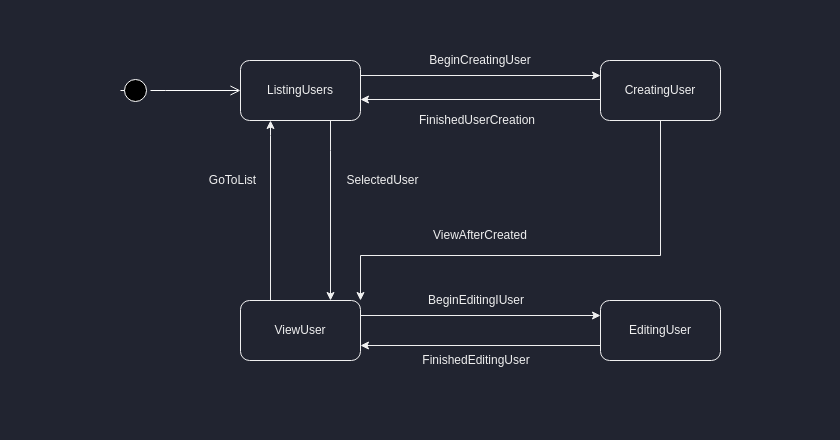

Instead, we can start using a state machine.

class ListingUsers implements State {}

class CreatingUser implements State {}

class EditingUser implements State {}

class ViewUser implements State {}

Commands and state

To get everything together, we can use a simple reduce.

/**

* Pattern matching objects by their contructor's

* name.

*/

function match(object, table) {

const name = object.constructor.name;

return (table[name] || table['_'])(object);

}

/**

* Given a state and many commands,

* integrate each and accumulate

* the next commands each command

* can issue.

*/

function updateState(state, commands) {

let nextState = { state, commands };

do {

const commands = nextState.commands;

nextState.commands = [];

nextState = commands.reduce(

(currentState, command) => {

const { state, commands } = currentState;

const [s, cs] = command.apply(state);

currentState.state = s;

currentState.commands = commands.concat(cs);

return currentState;

},

nextState

);

} while (nextState.commands.length != 0);

return nextState.state;

}

class ListingUsers {}

class ViewingUser {}

class CreatingUser {}

class EditingUser {}

class SelectedUser {

constructor(user) { this.user = user; }

apply(state) {

return match(state, {

ListingUsers: (s) => [new ViewingUser(this.user), []],

'_': () => {

throw new Error('cannot select if not on ListingUser state.');

}

})

}

}

class EditUser {

constructor(user) { this.user = user; }

apply(state) {

return match(state, {

ViewingUser: (s) => [new EditingUser(this.user), []],

'_': () => {

throw new Error('cannot edit if on ViewUser state.');

}

})

}

}

class CreateUser {

apply(state) {

return match(state, {

ListingUsers: (s) => [new CreatingUser({}), []],

'_': () => {

throw new Error('cannot create user if on ListingUser state.');

}

})

}

}

let list = [{ user: 'me' }];

let state = new ListingUsers(list);

// start at this state

state = new ListingUsers(list);

// transitioned to ViewingUser

state = updateState(state, [new SelectedUser(list[0])]);

// throws because ViewingUser

// can't handle SelectedUser event

state = updateState(state, [new SelectedUser(list[0])]);

This is great! We can now test it separate without having to setup anything related to the library or framework or whatever.

Also, if we use property-based testing, we can generate as many events as we can to test "infinity" scenarios.

The application state becomes just a lot of commands applied to an initial state.

It simplifies a lot because:

- everything is updated in a single pass

- user can issue as many commands as they want (still a single pass)

- most of the things are in a central place

- state transitions are clear

- this can be used to create feature/local state to control inner components on a use case

- it's also FRP-like (functional reactive programming)

And this idea comes from way back:

- Functional reactive animation - Paul Hudak, Conal Elliott, 1997

- Event-Driven FRP - Zhanyong Wan, Walid Taha & Paul Hudak, 2001

- Arrows, Robots, and Functional Reactive Programming - Paul Hudak, Antony Courtney, Henrik Nilsson, and John Peterson, 2002

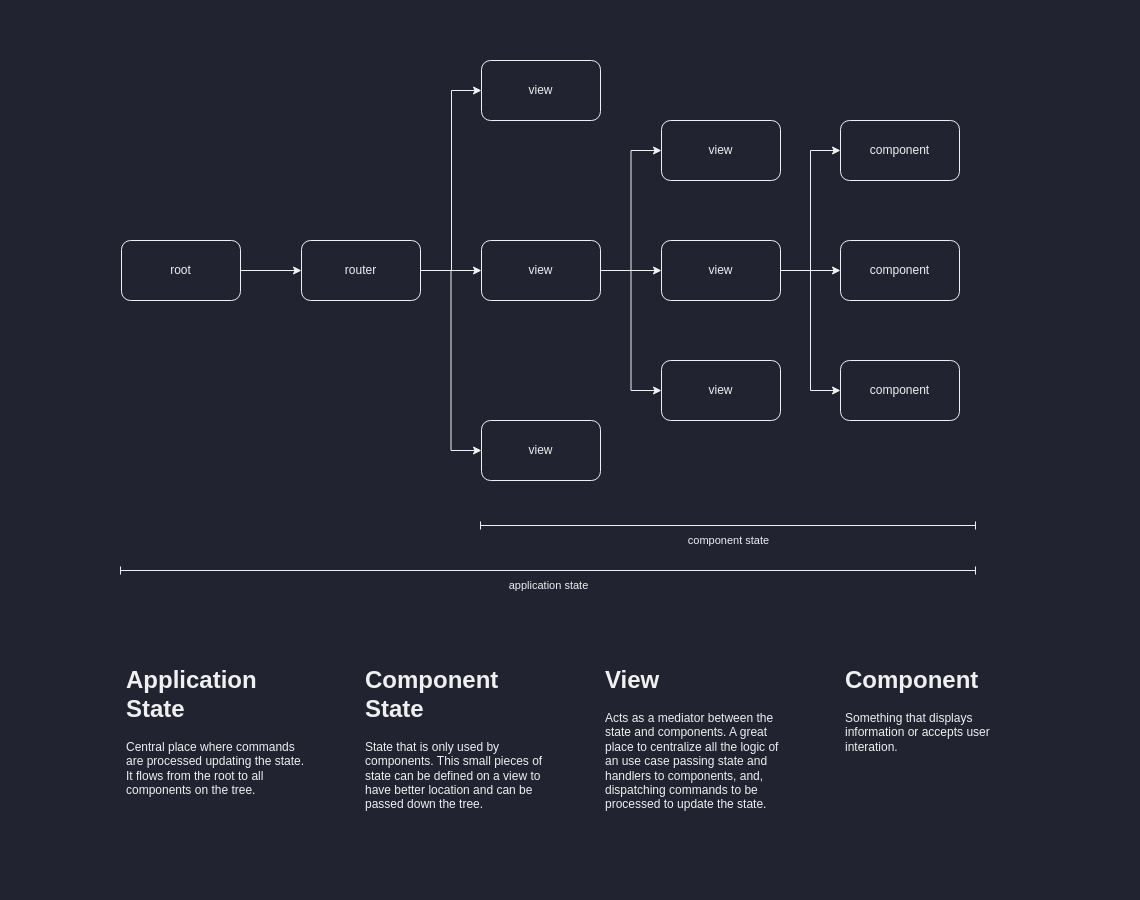

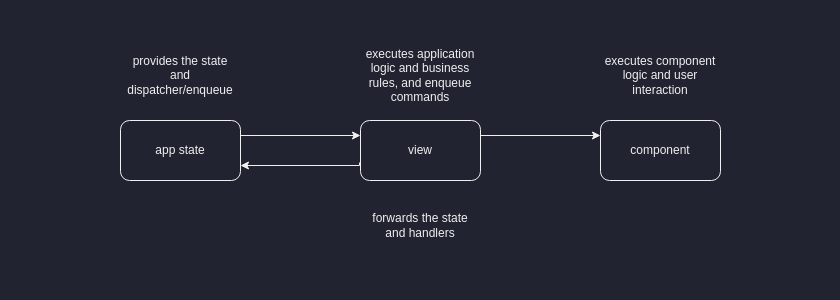

On applications, this is a very simple separation of concerns that may help you develop large scale apps.

The application flow is like: